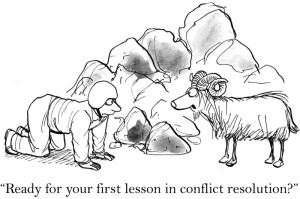

For the better part of the first half of my life I viewed conflict as something to be avoided. I grew up as one of the 84% of this world that are conflict adverse. I wanted to be liked and loved. In my head that meant avoiding conflict with people. My understanding about conflict went like this: Conflict shows up when what we want or think clashes with what someone else wants or thinks. Our primal instincts get threatened, and we try to protect our territory—our version of what is right and wrong, our opinion about what should happen next or our sense of entitlement to get what we want.

For the better part of the first half of my life I viewed conflict as something to be avoided. I grew up as one of the 84% of this world that are conflict adverse. I wanted to be liked and loved. In my head that meant avoiding conflict with people. My understanding about conflict went like this: Conflict shows up when what we want or think clashes with what someone else wants or thinks. Our primal instincts get threatened, and we try to protect our territory—our version of what is right and wrong, our opinion about what should happen next or our sense of entitlement to get what we want.

Because conflict taps into those deep instincts, it can feel like a personal attack. Depending on how situations were handled in our family of origin, our default response to conflict may be to fight, flee or hide. Those responses may feel comfortable to us, because they’re what we know, but they’re no fun. And so we may do just about anything we can to avoid conflict. We may agree to something we don’t want to do, give up something we want or avoid taking risks.

That was me.

I evolved from that thinking to an understanding that all conflict can’t be avoided. By my middle 30’s I reached a point where I could ‘tolerate’ conflict. As I continued to evolve into my 40’s I came to understand that conflict may feel uncomfortable but it can be positive. It can clear the air of resentments that have been contributing to toxic relationships. It can also highlight things, people or situations in my life that it was time to let go of.

By my mid-40’s I won’t say that I was ‘inviting’ conflict, but I was able to ‘hug’ it more often. It was also during this time that I began to understand the by-product of my conflict avoidance and how it influenced my ability as a leader. That was a necessary, but not a pleasant revelation. I became acutely aware of the number of ‘important’ even ‘critical’ conversations/ situations that weren’t being taken care of on a timely basis. I began to understand the impact of that non action – people were not receiving the information they needed to have greater clarity or improve their behavior or performance. If I was going to be a more effective leader, I needed to solve for my avoidance tendencies.

Facing conflict was an evolutionary process. It was a combination of awareness and practice that allowed me to accept the situation for what it was and to stand my ground and take the action required. I wasn’t successful all the time, but my ‘batting average’ began to improve. As I ‘emerged’ on the other side of conflict I found new confidence and a boost to my effectiveness as a leader. In several cases it also strengthened my relationship with the other person.

Changing our default response to conflict takes time, personal awareness and lots of practice, but it can be done. When we embrace conflict, we are able to see it in a more ‘rational’ light and be able to detach from it emotionally (at least that’s the goal). Instead of tapping into our primal instincts, we can access our “higher” self; our loving, wise, intuitive side. That part of us can always find a win-win solution, or a way to find the learning and opportunity in even the most difficult encounter.

The more we face conflict, the more comfortable we become with it. We can’t rewrite our family history, but we can re-learn how to deal with the inevitable phases of disharmony in our relationships.

Part of my evolution was to do three things:

- Choose my battles. Before embracing a conflict head-on, I decided was it necessary, and if so what was the timing. By getting out of my ‘emotional brain’ I was able to more fully evaluate what my response needed to be.

- Take a time out. At the first sign of conflict, I learned to check in with my level of emotional centeredness. If I was feeling attacked, and more emotional, I would find a way to disengage from the situation and get calm.

- Check in with someone else. Often, I would find a ‘trusted advisor’ to reflect, sometimes vent, my feelings to in order to create greater objectivity. I resisted the temptation to get the person to take sides; I focused on my feelings versus the details of who did what to whom. This helped me evaluate more fully the source of the feelings and figure out what I wanted to do about it.

Conflict is inevitable in our world. Different people, different styles, and different values all contribute to situations that can contribute to conflict. When we understand the inevitability of conflict as a leader we will be in a better place to deal with it. I hope you found my ‘evolution’ with conflict to be helpful in looking at your own abilities in this area.

To a better you…